Conversations on race and fatherhood

Photographs and interviews by OLIVIA ROSE

Chad Stennett, 36, Leyton

Father of Niyah, 14; Chanyah, 11; Aziyah, 10

I was 20 when I had my first kid. I felt young, but I had circumstances that made me pattern up, you get me? Now I’m shocked when I look back and see all these young guys — they ain’t got a clue. There’s no manual to this.

I was with their mum for 18 years, longer than most people’s parents have been together. Being with somebody for so long you get to a point where you understand each other. My thing is I’m always going to be part of their lives. Some people might not be allowed to come round to their children’s houses and chill with them, but I do. I put them to bed, cook them dinner and make as little disturbance as possible so they feel comfortable with the situation.

My dad disappeared when I was nine and I said I was never going to do the same thing. For me the number one role for a man in the family is discipline. You’ve got to show them authority from early on. And women’s roles have changed; they’re not just the housekeeper, they’re going out working. They might not notice as many things as mums who were staying home all the time. As a dad you’ve got to take some of that responsibility on board and listen, to notice what’s going on with your children in the household.

We’ve got different battles as black fathers with everything that’s going on in society and the media. Race is a massive issue. My children are young and they’re thinking about politics, and are worried about Donald Trump and Brexit.

If you start your history at slavery, then the kids are going to feel a certain way. That’s what school does. But if you teach them about the African kings and the great civilisations, it’s like “OK and then this happened”. Then they can understand that slavery is a part of a turn of events, when society fell. There’s a lot of good for them to learn aswell, there’s black history.

They have to know they are different. If you don’t, then the white man’s going to show them when he deals with them funny. So if you prepare them for that and tell them what the bigger picture is, then you’ve given them the tools to deal with it.

If I can leave my children a legacy it would be morals. I don’t want my daughters being used and I want my son to respect himself as the man he is. As black children, you have to know yourself, know your history and not doubt yourself, no matter what the media is telling you. It’s up to us as parents to tell them otherwise.

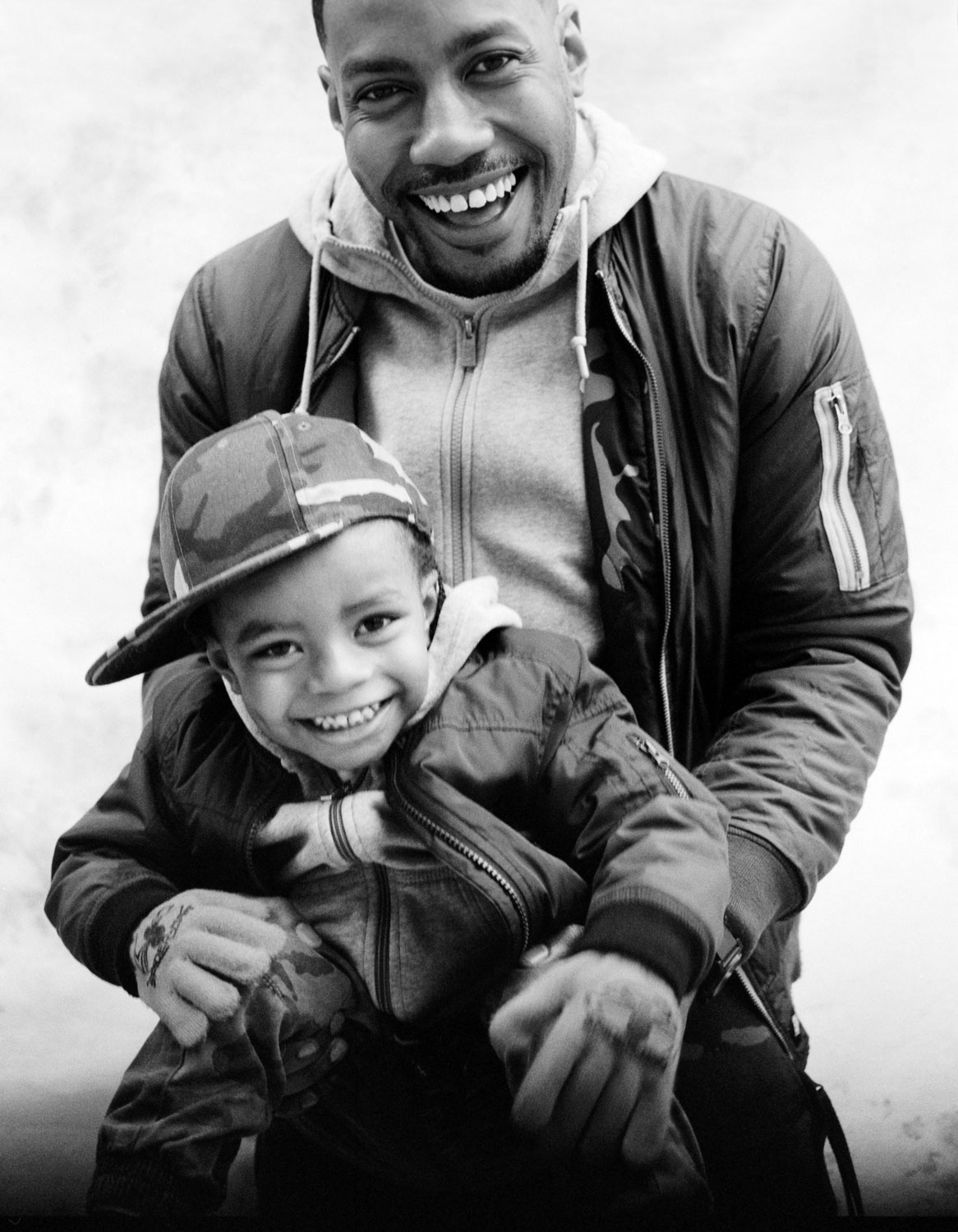

Jon Dundas, 26, Charlton, South London

Father of Bennett, 6

I was 19 when I had my son and I grew up quick. I don’t know when you’re ever ready to have a kid, but after he was born I realised I was doing so many things wrong, it was silly. It was a big shock, a big change. The way I handled money, the way I handled myself — it had to change. I think before him I was more self-centred, but now life comes with that sacrifice, when you literally put someone else before anything.

A lot of my friends have had kids young and it’s seen as a big problem. But I don’t really see what the problem with it is because I was just really happy. He wasn’t planned, and it’s complicated between his mum and me right now, but we all live together. When people find out I’m a dad and then find out I was with his mum for nine years, some people can’t believe it. I don’t know anyone else that’s been around for their kid like that to be honest, so I get it. It is a thing. I see absent fathers everywhere.

I understand sometimes why people get stereotyped. The way some of my friends act when they get a girl pregnant, that’s why other people think the way they do about us young guys having babies. I was one of the first of my friends to have a kid, and out of my close friends I’m still the only one with a kid. The mandem reacted like most guys my age do — they thought it was the end of the world!

I’ve had words with my friends about situations like this because I find it offensive the way they talk about it. It’s an immaturity to not stick with your child.

I try to do the right thing, it’s important for me. Even though his mum’s there, I feel like it’s my responsibility to get up and take him to school. As a dad you have to be there always and bring the security. It’s not always about bringing in the money, because when you have a partner it’s a joint thing, but it’s about love. Love is the one thing I want to pass on to him. I view the world and people with a lot of respect, and I hope that he grows up to be like that. I hope he sees things the way I do.

I love hearing that word — “Dad” — when they call you. When you’re sitting there and you hear that “Dad, Dad, Dad”, that is one of the best feelings ever. When you hear people complimenting your son on his intelligence or his looks, things like that, that’s one of the proudest moments, because that’s my son. That’s my boy.

David Nkrumah, 30, Bethnal Green

Father of Zion, 2 months

It wasn’t planned, but when Geraldene told me the news we embraced it. I couldn’t wait to see her belly grow to this stage and I’m excited, really excited. I’vealways known that my first child was going to be a boy and when I found out that was true, it felt like it was meant to be.

After the baby’s born we are having an African naming ceremony. It’s Ghanaian tradition. The baby is blessed with a name that will give him protection, good health and strength. I’m not that into the custom, but I want him to know his heritage. I didn’t get to appreciate my roots until I got to my teenage years and I started to understand that I’m not from England, I’m from Ghana. When I went to Ghana and saw all these people who looked just like me, it made me understand that it was who I am. Now it’s cool to be African, so I want him to be proud of his roots.

I think a dad’s role is to be active and supportive in the child’s life, through everything; cook for him, clean for him, educate him. Everything that the woman does the man should do as well. I’ll dive right into the nappy changes! It’s important to teach him how to be a man in this society that we live in, and to teach him how to be a black man. He needs to be taught how things are and he shouldn’t have any limits or feel like he can’t do whatever he wants to do. Even if we don’t have the money to do everything we want, he’ll be all right. I grew up with the bare minimum and I turned out OK.

I don’t feel the pressure of being a dad, it feels like a normal thing to do. Where I grew up, lots of people didn’t even have fathers, but I don’t feel like the people I know have that same thing in them to abandon their child.

I would like to be able to teach him beyond what I know, education-wise. I’ve been thinking about trying to revisit certain subjects, like maths and English, so I can help when he gets to that higher stage and comes back with homework. That’s what’s been going through my head — how to teach him things that I don’t know about. I’ve got to do some research and learn things myself so that he can become better than I am. I’ve still got time!

People say that I’m warm-hearted and polite, so I would love for him to share that trait. It will represent me if he had that same glow. No matter what, if he doesn’t have any money or things aren’t going to plan, I want him to never give up and to always keep smiling.

Rene Francis, 31, Plaistow

Father of Amayla-Rae, 3

When I found out I was going to have a baby I was shocked because it wasn’t really planned and my partner was in a different country when she found out — she phoned me from Cyprus. I was just there at home alone, like, “What?! I’ve got a child coming?” Obviously I was scared, but what made me even more frightened was when I found out that it was a girl. That’s when I was worried. I thought: “Oh no I’m gonna have to go through a lot of stuff now!”

I think maybe I sussed out what to expect before she was born because I’ve got little cousins who I’ve seen grow up. The only things I didn’t know were the nappy changes and waking up late at night. I knew it in my head, but then you experience it and you’re like, “Wow, OK, this is what we go through.” I was there for all of that. We were together at that time, me and her mum. Now we’re not together, I don’t see Amayla-Rae as much as I should. It’s crazy because every time I do see her, every time she stays the night, it’s like she’s a different person. She’s learnt a lot more, she’s talking a lot more frequently.

I’m going to be in her life as long as I’m alive so I’m just trying to stay close to her. If you get too strict they hide things, so I’m just trying to keep a good relationship with her. I’ve got to stick at it; it’s not going to be easy.

I want her to grow up to be a strong, powerful, confident lady. A lady, you know, not riff raff. The way society is now, I don’t want her to be stuck in that stuff day-to-day — you know the girls that go out partying and are into make-up and take all them selfies — I just want her to be herself and not give in to peer pressure. The thing about her is she’s cheeky, but she’s really advanced and smart, so I can talk to her normally and she’ll understand what I’m saying. But when she gets to that stage where she’s like “no, no”, I don’t know what’s going to happen then.

A dad’s role? Oh gosh! Guidance? Protection? I guess it’s showing her the rights and the wrongs in life, what paths to take or not take. With men trouble and that, she’d go to her mum, but we haven’t got to that stage so I don’t know how to deal with it yet.

I think everyone wants to be a better father or do better for their child than how their dad did. You just want the best for your child. My dad was always around, but not so much for me. I’venever actually gone to my dad for advice and I would be shattered if my daughter said that about me in 20 years. I would love for my child to say that we have a good strong relationship, we’re close, I can tell my dad anything… things like that. Then you know you’ve done all right, haven’t you? If your child can talk to you and tell you her problems then you’ve done all right.

Aaron Williams, 31, Bow

Father of Kairo, 2

When Kai was born he didn’t cry at all. He was chill, like his Pops. I sang You’ll Never Walk Alone to him and I shed tears. He came out healthy as fuck — 8lb 2oz, a solid strong yout. His first skin to skin was with me; he was still bloody but it didn’t matter. This was my little boy!

About five minutes later he let out a little whimper and he wasn’t feeding, so the nurses took him. Suddenly he had tubes in his hand and nose, and he was in an incubator because he had swallowed amniotic fluid. By the third day in hospital we still hadn’t named him because we were just concerned about getting him home.

You don’t know how to be a dad until you’re forced to do it. The first week he was alive I probably had about ten hours of sleep. They prepared us for the worst, but in the end he fought off the infection himself. We had a few names floating about — like Royal, King, Rain — but Kairo was the one that stuck. It means victorious. From birth he was fighting.

I learnt how to be a father through my mum. She worked two, three jobs while she was alone with four boys. When my mum remarried, I thought that my stepdad couldn’t offer me everything because we weren’t blood-related. My brothers and I couldn’t get our heads around it because we were young and it was like, “Ah, he’s white though!” Wewere resentful because my dad wasn’t around. But my dad was an extremely bad partner — because of him my mum doesn’t have any of her original teeth. But I still can’t say I hate the guy, because that would be poisoning to me. I have to break the mould.

I know one thing: I’m going to be a better man tomorrow than I was today because of my mum, and because of my son. My mum is the truest G. I never understood that until Kairo was born and I was having to hold down the fort. She’s the best woman I’ve ever met in my life and I love her to death. If Kairo feels about me half of what I feel for her, I’ll be super happy.

I’m doing youth work at the moment. It’s my way of giving back to the community I’m from and trying to show them there is a way out. These youngsters have told me all sorts of stories of people losing their life over stupid shit, just because they’re not from the right area. One of the major problems is ignorance. If these kids ever sat down and spoke to each other they’d understand they’re the exact same people.

The common denominator is the lack of positive male role models in these young people’s lives. That taught me that I have to be there 100 per cent with my son. As a young black boy he needs somebody to look up to who looks like him, who’s also doing positive things.

Kairo has completed me. I’d lay my life down for him. Nothing compares to having to give a shit about someone else for the first time. I love the boy so much. Creating life is the most important thing I’ve ever done. I’m not trying to be this big superstar. As long as I’m a good dad to him, that’s a success to me.